The technique

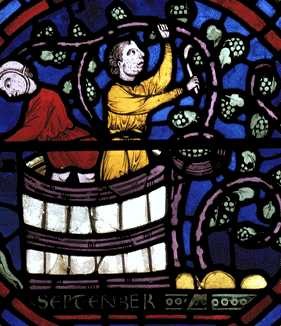

Stained-glass art is unique because of the relationship that exists between glass and light. The colour we see in a stained-glass window is brought to life by the light refracted through it. The colour of a stained-glass window changes according to the time of day, the seasons and the weather.

Stained-glass art is unique because of the relationship that exists between glass and light. The colour we see in a stained-glass window is brought to life by the light refracted through it. The colour of a stained-glass window changes according to the time of day, the seasons and the weather.

The technique and processes of making a stained-glass window have changed little from medieval times. The main differences stem from technical innovations and improvements such as steel-wheel glass cutters instead of the old dividing iron, gas and electric soldering irons and stained glass kilns.

Measurement

- Sketch

- Cartoon

- Cutline

- Choice of glass

- Cutting the glass

- Aciding, painting and silver stain

- Firing

- Leading-up

- Banding and installation

Measurement

The first step in the making of a stained-glass window is usually a visit of the building for which the window is to be designed. The exact size and shape of the opening, whether of stone, wood or metal, must be ascertained and faithfully reproduced on paper. A plumb-line determines the window’s perpendicularity. Measurements are then made of the overall height, the height from springing line to base, the position of the glazing bars, the width and the mullions. If possible, the artist visits the building to soak up the atmosphere, the style and aims of the overall architectural conception. He observes and notes the position of the window in the building, its aspect, the trees and buildings outside, and the strength of sunlight too must all be taken into consideration before the artist can start his work.

Sketch

The next stage is the preparation of a small coloured drawing, usually to a scale of about half an inch to one foot.

This drawing, called sketch, or design, is done in watercolours and inks and gives an accurate impression of how the artist visualizes the finished window. The degree to which the sketch is perfected depends upon the artist’s method of working, but it must be sufficiently precise for it has to be enlarged to the actual size of the window, photographically or by a process known as “squaring-up”. This is done by placing a grid on the sketch and an equivalent scaled-up grid on the cartoon, so that the main lines and masses can be positioned correctly

Cartoon

The cartoon is the full-size working drawing for the stained-glass window which traditionally is drawn by hand. All the dimensions and details must be exactly right. Bold black lines of charcoal represent the leads, and shading suggests later painting on the glass. The saddle-bars and division-bars also have to be marked in the cartoon.

In early medieval times, stained-glass artists drew their cartoons on white-washed boards, which were easily transportable : the board was to be whitened all over with chalk, and then the lead lines were traced out in the wet chalk.

A further full-size drawing must now be made to enable the glass-cutter to do his work and for this a tracing is made from the cartoon.

Cutline

The cutline is a tracing of the lead-lines of the cartoon, which forms the pattern from which the pieces of glass will later be cut. It shows only the shapes of each piece of glass and the lead-lines. A sheet of tracing paper or tracing linen is placed over the cartoon and a pencil line is drawn down the centre of each lead-line.

The artist usually numbers each segment of the cutline and indicates the colours. The glass is then cut directly on the cutline. In the so-called template method, the cutline is not retained intact. It is drawn on thick tracing paper or transferred from thin tracing paper to stout card, marked and then divided into its component pieces with either a two-bladed knife or special three-bladed scissors which cut out thin strips corresponding to the lead cores. The cut shapes of card, marked with colour and panel reference, are used as templates around which the glass is then cut.

Choice of glass

The artist choosing the glass refers to his original small coloured sketch. He can select among an almost infinite palette of colours and several glass qualities. Almost any kind of glass – even ordinary commercial glass – can be used in stained-glass windows today, but the most commonly used glass is muff glass : a blob of molten glass is picked up on the end of a blowpipe and blown into a bubble. It is then elongated by swinging to the form of a cylinder which then is split along its length, after the top and the bottom having been cut off. In a hot kiln it is then opened to a flat sheet. Crown, or spun, glass is rare today, but was widely used in early times : the round twirling bubble of blown glass is attached at the nub to an iron rod, the blowpipe is cut off, leaving a hole. The rod is spun rapidly and the hole is widened with a stick. The glass flares out to form a disc with a central knob, or bull’s-eye. These two types of glass are classed as antique.

The hand-made antique glass differs from ordinary machine-rolled window glass in its variations of thickness and texture. Small flaws which concentrate or diffuse the light create a fascinating and ever-changing shimmer and iridescence and it is for that reason that stained glass is still manufactured as it was in medieval times by a process which encourages imperfections. The main ingredient of almost all glass is silica, which may be sand, quartz crystals or flint, and to assist it to melt, a flux, usually soda ash or potash, must be added. To resist moisture, a stabilizer of either lime or lead is necessary. The whole is then heated and melted at a temperature of about 1500 degree C. Cullet, or scrap glass, is sometimes added to assist melting. Glass made from a pure mixture of silica, soda and limestone is nearly transparent and colourless. To colour glass, extra substances have to be added : metallic oxides are mixed in the substance of the glass which then will be called pot metal glass (the pot being the steel-lined vat where the molten glass is kept in flux during the blowing of the antique), because it only needs to be made from one pot of one colour.

The following colours are obtained by the metallic oxides indicated :blue : cobalt and chromium ; red : selenium and copper salts ; yellow : selenium and chromium with cadmium salts ; green : copper and chromium salts ; purple : manganese and cobalt. Impurities in these oxides lead to a very wide range of colours. Usually, muff glass is pot metal glass, but a light-coloured glass can be tinted by a thin layer, the flash, of deep colour : the two layers of glass are blown out together, by the blower first collecting a very small amount of deep colour on his blow-pipe and then progressively building up a thick layer base colour or white. Certain colours are essentially flashed glass. Red is nearly always flashed when it is not coloured with selenium ; greens are frequently flashed, and blues may or may not be.

Flashed glass is used when two colours have to be shown on one piece of glass. As in stained-glass windows all the colours are in the glass itself, the choice of glass is critical and so important that a great deal of time and effort is spent to it.

Cutting the glass

After the glass has been chosen, it is usually cut to shape by an experienced craftsman. Today, the main tool for glass cutting is the steel-wheel cutter, diamond cutters being difficult to manoeuvre and only used to cut straight lines. They have replaced the medieval dividing iron which cracked the glass with its heated tip.

Glass is cut to shape either on top of the cutline or around templates. In the cutline method, a steel-wheel cutter is run over the glass on top of the cutline, leaving a thin incised trail. In the template method, the template is placed on the glass and the steel-wheel cutter is run along one side of the pattern. Glass is a material that has to be cut in two stages. First a line is incised, which starts a fracture. This line, or trail, is then deepened either by hand pressure or by tapping, and the glass divides. When glass has to be cut in deep curves, first the full curve is outlined with the cutter, and then a series of small incisions is made. It then is grozed so that the edges are slowly nibbled away to produce the required shape.

Square-ended pliers have replaced the old grozing irons, which were used by the medieval craftsmen to nibble the glass to shape.

As each piece of glass is cut, it is wiped with another piece of glass to blunt the razor-sharp edges.

Aciding, painting and silver stain

Aciding, or etching, is the process of removing the coloured layer, the flash, from flashed glass which consists of a layer of white or light-coloured glass with a thinner top layer of a darker colour.

Those areas of the glass which are not to be acided, including the back and the edges, are coated with a protective layer of beeswax or bitumen.

The glass then is immersed in a bath of dilute hydrofluoric acid. The medieval artist ground the coloured layer away using powdered stone as an abrasive.

The next step is to attach the newly cut and acided pieces of glass to the easel, ready for painting. The easel has a plate-glass frame to which the pieces of glass are fixed with melted beeswax.

The main aim of glass-painting techniques is to control and modify the light coming through the window. The paint used is dark-brown vitreous enamel. It is used for shading and for linework and in washes, or thin coats of paint, which tone the colour of the glass. The effects possible with the glass paint range from a heavy line to subtle modelling and to modern free brushwork and textures, having been adapted from today’s painting. Usually, the paint is applied with a flat brush as an initial, even wash of paint which, while still wet, can be gently brushed or whipped with the long-haired badger to make a dull matt. It also can be stabbed with a badger or with a stippling brush to make a stippled matt. When the shaded wash has dried, it can be further lightened with short-bristled scrubs.

Delicate details usually are traced from a cartoon with a fine liner brush. For broader lines and spatter effects, soft and Chinese brushers are used. Another important technique is removing or “picking out” the paint, generally with needles or sticks, to allow the light to penetrate as white areas. The paint is basically finely ground iron oxide and powdered glass, mixed with borax as a flux. When heated in the kiln, it fuses with the surface of the glass. To make the paint adhere to the glass, it is mixed with water and a little gum arabic.

The main linework is usually traced from the drawing beneath and instead of water, used for the shading and toning, a dilute solution of acetic acid is used as the medium, the advantage being that, when dry, the acid line is resistant to water, so that the next stage of painting can be done on top of the acid paint.

After most of the painting has been done, the next stage is the application of silver, or yellow, stain, which generally is painted on to the outer surface of white glass because unlike paint, it is not affected by weather.

The stain, from which the generic name of stained glass is derived, is a mixture of silver and gamboge with a little gum added. The action of the silver is that it changes the ionisation of the glass, causing it to filtrate yellow light instead of the white or coloured it previously did.

The staining of glass depends on the disposition of the individual coloured glass to take stain, the time and the heat in the kiln.

Firing

After the glass has been painted, it is fired in a kiln. Firing is the process of heating the painted glass so that the paint and glass are fused together. For firing, the glass is laid out in iron trays, each with a layer of powdered plaster of Paris carefully smoothed to provide a level surface for the glass. As moisture or air beneath the glass can have damaging effects, the plaster is thoroughly dried and tamped down solidly.

Types of glass which need the same firing go together. All hard glass – greens, blues and tints – are put in one tray and all soft glass – whites and yellows – in another, so that the firing can be suitably adjusted.

For proper firing, the glass must be gradually heated to about 600 degree C and kept at this temperature for up to fifteen minutes so that the paint and glass can smoothly and securely fuse together. It is then slowly annealed, or cooled.

Great care must be taken to avoid cold draughts of air reaching the hot glass, as any sudden change of temperature may cause the glass to crack or even shatter.

Leading-up

Leading-up is the assembly of the glass into leads and is done on a wooden bench with the cutline or templates for guidance. First a wooden right-angled frame is fixed to the bench to hold firm the side leads of the panel. A lead is then stretched, cut and put in place. Glass is inserted and more leads added. Nails hold every piece of glass tightly in position. Once in place, the soft strips of lead are cut to the exact length with a special cutting knife. The lead is tapped with the handle of a stopping knife or a hammer to fit it to the glass.

Adjacent pieces of glass are set into their positions and more leads are cut and pressed into place. The process continues until all glasses are asssembled together.

Leads can vary in shape and depth, but their core is almost always one-sixteenth of an inch wide. Viewed in cross-section, a lead strip looks like a sideways H, and the glass is inserted into both sides of the lead so that it touches the centre.

In medieval days the leads were cast on the spot. The craftsmen poured hot metal into boxes lined with reeds, called cames, and that name is still in use for a length of lead. Modern leads are cast in iron moulds and shaped by a lead mill. When all the panel is completed, the joints between the leads are pressed together, cleaned and rubbed with tallow which acts as a flux. Then the leads are soldered to make a permanent joint at the places where two strips of lead meet : a stick of blowpipe solder is applied to the joint and a blob is melted into place with a hot, copper-tipped soldering iron. When all the joints have been soldered on one side, the panel is turned carefully and the process repeated for the other side.

More recently, cement is used to fill the space between the glass and the leads, to prevent the glass from rattling, and make the whole panel waterproof. It also seems to strengthen and rigidify the panel. The cement is a mixture of powdered whitening, and plaster of Paris to which some lampblack, white spirit and boiled linseed oil are added. This porridge-like cement is pushed into the crevices between the lead and the glass with a stiff brush.

After several days the putties have set and the panels are ready for banding and installation.

Banding and installation

Stained-glass windows conceived for large buildings hum and vibrate under the pressure from the wind, so that they have to be composed of several panels joined together by iron glazing bars that cross the window horizontally. To held the panels in place against these glazing bars, division ties are soldered to the panel at the edges. This process, which comes last of all in making a stained glass window, is called banding or wiring. Bands may be made of lead, copper or zinc and are fixed to the inside or outside of the window, to be wrapped round the saddle-bars going across the window and twisted round themselves on the outside of the bar, thus hugging the bar and the stained glass to each other.

The stonework into which the window fits has either grooves or L-shaped channels, rebates, in which the panels are carefully slid in. For windows with grooves, one side of a panel is inserted deeply, the panel is then straightened and the other side is eased into position. The panel is then centred so that both sides are held by the stonework. The final step is always cementing the window into place so that it is firm and weatherproof.

For very large windows, iron or bronze T-bar frames with bars embedded in the stonework are used throughout the world. The panels rest on the centre of the sideways T and are held firm by another frame and a key. To give extra rigidity, bars are tied across the panels.